Mormon Share > Teacher (adults)

Tag Archive: Teacher (adults)

Scott Knecht

September 14, 2014

Would you like to know why most students won’t answer your questions in class and in fact are hesitant to participate in discussions at all? It’s because for the bulk of their educational lives they have been asked questions that need a specific answer and they have learned to be very hesitant about raising their hands to offer a simple thought. Even if they are semi-sure that they know the answer, they also know that the possibility exists for error and they will probably be wrong and the teacher will not hesitate to point it out. When they (or you or me) are publically called out for being wrong we will hardly try again; hence, the resistance to classroom participation.

But students almost always have something to say and it takes the right kind of question to bring it out, and it takes the right attitude from the teacher to bring it out. The attitude is this: “I know you have something to say and I really, really want to hear it.” But the teacher can’t just say that; it has to be demonstrated. You have to show them that attitude.

The right kind of question is the one that requires a response rather than an answer. An answer is a very specific type of response that corresponds directly to the question. Think of a math class (“The square root of 16 is…?”). There is only one answer to that question. Think of a science class (“The 15th element on the periodic table is…?”). Only one answer will do for that question, so we watch students furrow their brows and puzzle over it, looking down and hoping not to make eye contact. Very few are brave enough to answer and when no one does the teacher continues to assume that questions are not very useful in class and “I should just stick to my lecture notes.” So much for questions that need an answer. They rarely bring one and when they do it comes without much thought.

But what about asking a question that begs for a response? A response is any comeback that keeps the conversation going. It could be an attempt to directly answer the question, but it could be a follow up question from a student, or simply a thought, or a wonderment. What if the teacher asked the kinds of questions to which there are no wrong answers? How about this one: “The Russians launched an earth orbiting vehicle before the Americans, but the Americans were first on the moon. Why?” There could be lots of reasons and lots of thoughts about that, but all can participate safely.

Here’s another one: “Joseph Smith received his first vision in 1820 but the church wasn’t organized until 10 years later. What was happening in those 10 years that made the wait necessary?”

Often you can start a question with this simple phrase: “In your opinion…” There is a slight danger with that question because you don’t want to create a huge pool of shared ignorance, so the teacher needs to listen and guide and help reshape the responses, but everyone can eventually share an opinion.

I read of a science teacher who gave each student a barometer and asked them to use it to discover the height, in feet, of a certain tall building. I suppose there are a lot of useful scientific ways to figure that out but the one that intrigued me was the student who had the correct answer and when asked to explain his method said, “I went to the building superintendant and told him that if he would just tell me how tall the building was that I would give him the barometer.” The teacher’s original question created enough room that a wide variety of thoughts and responses were acceptable.

So if you want to get students talking in your class – and it works for both adults and kids – stop asking them to recall names and dates and numbers. That closes the door very quickly. And please stop asking this question “What did we talk about last time?” I can barely remember what I had for dinner last night. I just know that it was good and I liked it but I generally can’t recall it on cue anymore than I can recall the content of yesterday’s lesson (or last week’s). If you need to spend a brief little time reviewing what you did last meeting, just ease them into it by reminding them – “Remember yesterday that we talked about some of the main reasons America entered World War II? The reason that I thought the strongest was….. Which was yours?” As you ease them into it, they will remember and start to talk and then you can begin asking them questions that really generate thought and discussion, questions that need responses not answers.

Scott Knecht

September 11, 2014

The question I am asked most frequently about teaching is this one: “How do I come up with good questions to use in the classroom?” This is a critical skill for a teacher to have because, “To ask and answer questions is at the heart of all learning and all teaching” (President Henry B. Eyring). It would seem a simple thing to ask a question in class, and it is if you aren’t too particular about what follows. If, however, you want to stir up thinking and created a lively learning atmosphere in your classroom, you will need to learn how to craft excellent questions.

When a person tells me about their inability to come up with great questions, my first response is always the same: “You can’t come up with good classroom questions because you don’t ask good questions as you read the material in preparation for the class. You simply read the material.” Most people read a text just to read it. A teacher needs to read it and think about how to use it in class. I find that the most effective way to do that is to ask questions of the text as I read it. Here are 3 examples:

1. I remember the first time I read the Iliadas an adult (this did not happen as I read it in high school because I just sort of faked my way through it). I was struck with the opening line: “Sing O Goddess, the anger of Achilles…” Why was he so angry? How did his anger reach a point where it caused multiple deaths (which the line goes on to say)? Why is this the very opening line of the story? I was full of questions from just those seven words and I read awaiting the answers from the text. Those are questions that could launch a discussion.

2. This summer I read a book entitled “Empire of the Summer Moon” about the Comanche nation in North America. For 150-200 years, up to about 1880, they were the undisputed rulers of the great middle section of the continent, from Texas, and New Mexico on the south up through Kansas and Nebraska. They were fierce warriors, incredible horsemen, and ruled their territory. Their power kept the Spaniards from moving further north from Mexico and the French from moving west out of the New Orleans area. Both groups wanted to keep colonizing but were bottled up by the Comanche protecting their lands. As I discovered that insight in the text, I started asking questions: how did that help or hinder further migrations by different people? What caused the demise of their power and did that hasten migration? How different would America be today if the French had colonized much further west, or the Spaniards farther to the north? Can you see how questions like that could really enable discussion?

3. When I read the scriptures I am full of questions. Recently I was reading in Luke 17 and found this in verse 5: “Lord, increase our faith” and immediately I wondered what is the way to increase faith? So I read the subsequent verses slowly and found that in 6-10 He uses a story to outline one way and in verses 11-19 He shares a second way to do it. I would have never seen that if I had not asked a question of the text.

If you struggle to come up with good questions try doing this – have a conversation

with the text as you read through it. The three examples above all could have just been an ‘ooh and ah’ moment in the reading but I asked questions and was stirred up. Be full of wonder. Think deeply. Probe and push and pull. The questions that bubble up as you read can be turned into good questions that you can ask your students in class.

I’m going to devote the next couple of posts to the art of asking questions, both how to do it and how not to do it.

Scott Knecht

September 7, 2014

What do you think of this sentence: “The teacher is the architect of the learning experience”? I like it a lot. It’s been with me so long that I can’t recall if I thought of it (maybe) or I read or heard it somewhere (more likely). Either way, it expresses a truth about the classroom and the teaching/learning dynamic.

An architect has a vision, then commits that vision into detail on paper, and finally directs the execution of the vision. What he doesn’t do is all of the work. There are lots of people down the line that labor in realization of the vision, but the vision and the details begin with him.

A great teacher begins with a vision of student learning (not teacher performance) over the course of the term and for each daily lesson. The vision is “what will my students learn” and the details are “how will they learn it.” Start with a plan, fill in the details, and then be prepared to modify along the way, if the occasion calls for it. You’re the architect; you get to pick the materials to use and the quantity. For example, student participation is one of the materials to aid in the learning process. It is not the final product. Don’t get fooled into thinking that just because students are participating that they are learning. They may or may not be, but if you’re not careful, you’ll perceive participation as an end, not as a means to an end. The end we want is learning, and participation is useful because it opens up thinking and thinking causes learning. So we love to see hands go up to respond, but here is a truth that is hard to grasp: not everyone that raises a hand needs to be called on. If I ask a question and five hands go up I won’t necessarily call on all of them and I generally won’t do it in the order they raised their hands. If the last hand up is a student who doesn’t talk much, that’s the first person I call on. She needs to be heard and a variety of voices generally makes for a better class. And if I think that after 1-2 comments we have stirred the pot successfully and people are thinking, then I move on because as the architect of the learning experience, I get to select the materials (in this case, participation) and the quantity (how many students I call on).

You might assume that students will be offended if they are not called on, but here is another truth: when you raise your hand it is a sign that you have had some thoughts, that you have been stirred up sufficiently so that you want to participate. Whether you vocalize it or not you still have had the experience of thinking and that enhances learning. And if a student really has something to say that needs resolution, she will let me know by her persistence and she will get her say.

Great teaching is not delivering a boatload of new facts. It is the ability to stir things up in the minds of students so that they think and begin to see things in ways that maybe they hadn’t before and thus learn. When the Savior taught the two men on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:13-35) He expounded all things unto them, spent time with them, and then left, leaving them to ponder and wonder and grow in learning. He may not have answered all of their questions but He stirred them by leaving some things unsaid.

It takes a classroom architect with vision and skill to make that happen in a great teaching way that leads to great learning.

Scott Knecht

September 3, 2014

I walked into the first day of a 10th grade history class at Bellflower High School. The teacher took the roll and then said this (not an exact quote but an adequate paraphrase):

“I am Mr. …… I am the teacher, you are the students. My job is to teach and your job is to learn. I am not here to be your friend, just your teacher.” This was not good for me. I was 15, had acne, very little self confidence, and was just trying to fit in. I was not cool – that social level was always just out of my grasp. But teachers had helped cover up my social deficiencies by being my friends. From kindergarten through the ninth grade I had many really good teachers and never had I been told, right up front, that I should not expect some level of friendship. I quietly revolted by deciding not to be his friend, and not to do much of anything in his class.

Is it necessary to like students? I say yes and I would further add that it is critical to love them, to care about them, and to be concerned about them as people not just numbers (that is, if you want them to learn anything). Someone told me once that a good working definition of ‘charity’ (real, pure love) is to love the unlovable. I like that. It is easy to love the lovable – the students who come in with work done and with eagerness to do more, the pretty ones, the handsome ones, the smiling ones, the confident ones. It is much harder to love the unlovable. Those are the surly ones, the bored, the disengaged, the lost, those that drag in late and stare at you and dare you to teach them. The easy thing is to emotionally dismiss them and just work around them. The hard thing, and the right thing, is to find a way. Work your way into their life.

I’ve heard a teacher or two say something like this: “They don’t show any concern for me and I really have all I can do to work with the ones that seem interested.” If you are going to wait for students to show interest in you first you are going to wait a long time. That is not the natural order of things. In the New Testament, I John 4:19 we learn the proper order and it is this: We love the Savior because He first loved us. The person with the most power in the relationship has to begin the process. Sometimes the process is quick and often it drags out but I can hardly recall a student (teen-ager, young adult, or adult) that I could not be friends with, and then learn to love, after I made the first move and stayed with it in a variety of ways until we were friends.

Scott Knecht

September 1, 2014

I love the process of teaching. I love to think about teaching, to prepare lessons, to stand in front of a class and watch things get stirred up, and finally I love to watch the light bulbs come on and see students begin to understand something t…

Jennifer Smith

March 21, 2014

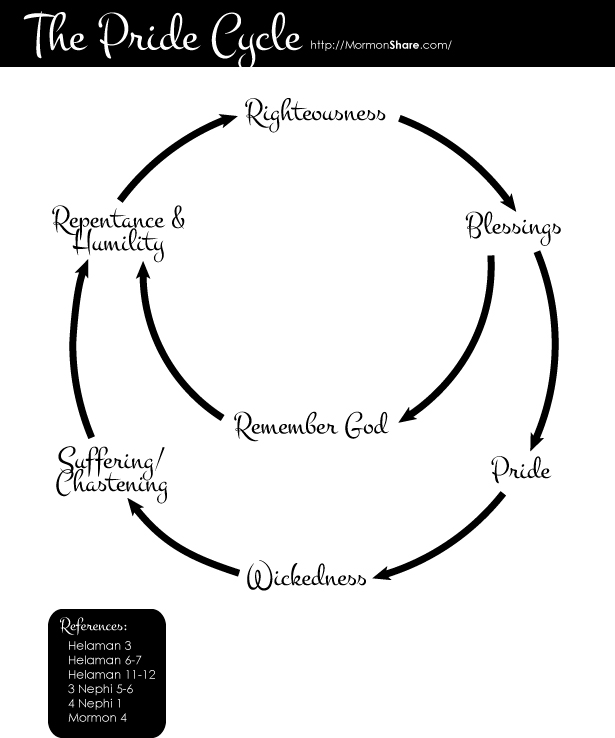

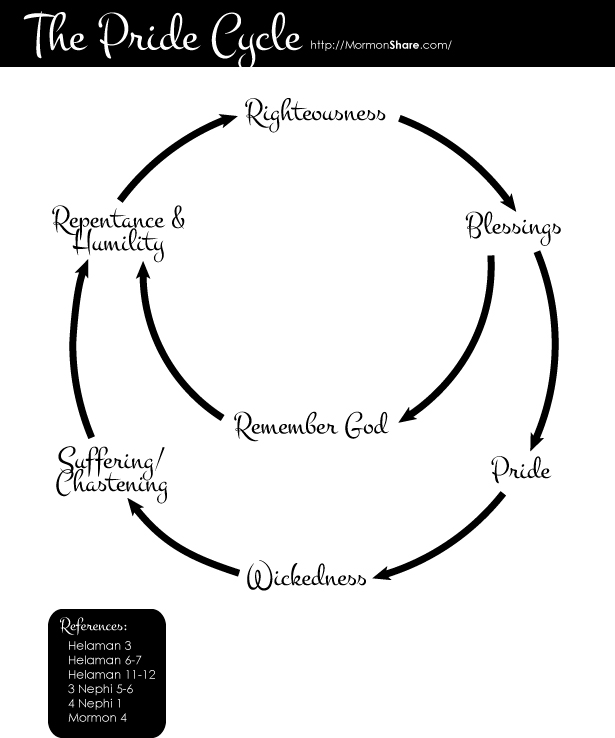

Here’s the pride cycle of the Nephites with the way of breaking free from it (remembering God) from Helaman 11-12. I’m using this handout for students to fill out the center portion with ways they can remember God and avoid pride.

Jennifer Smith

December 31, 2013

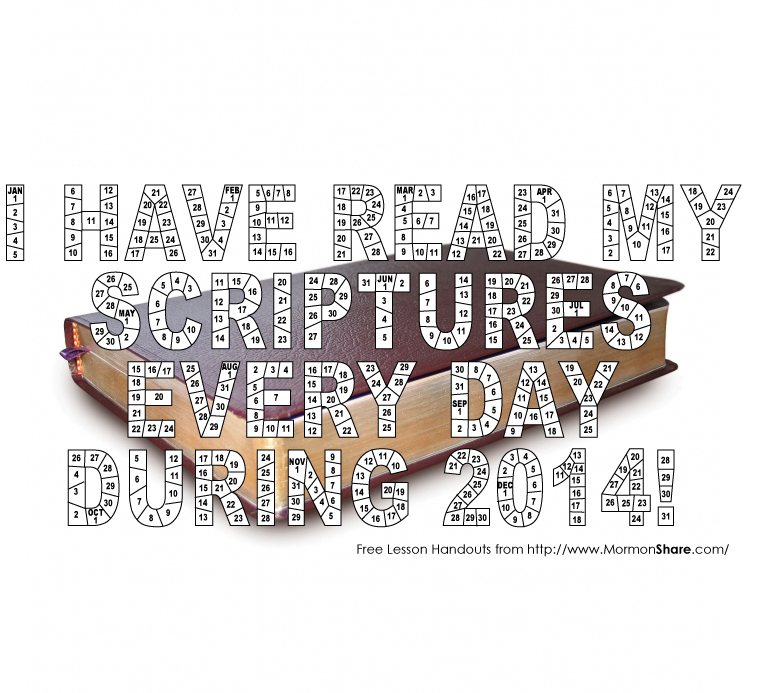

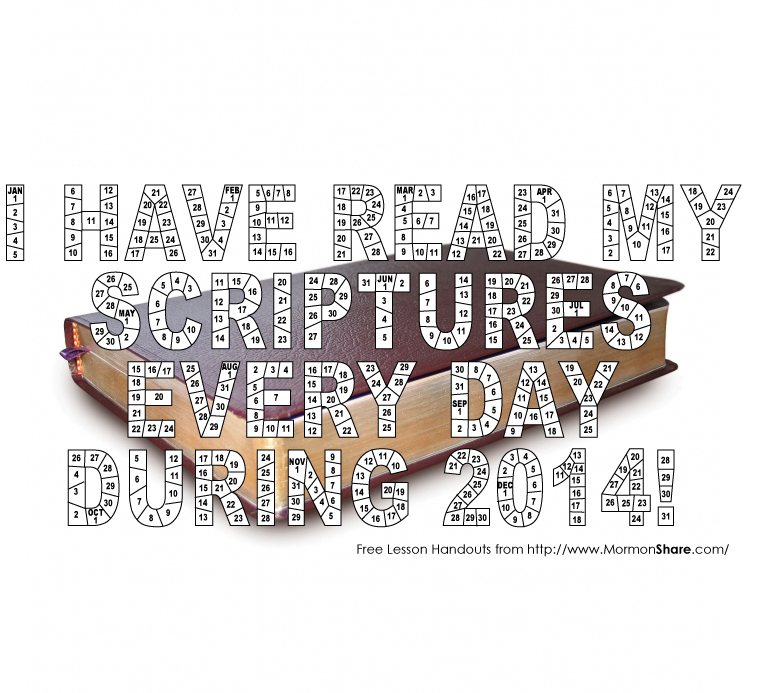

Here is the 2014 scripture reading chart reading “I have read the scriptures every day in 2014”! Enjoy! With or without scripture image. Also available as a plain 2 per page version.

LDS Printables

2014 mutual theme, 2014 primary theme, 2014 scripture reading chart, Activity Day Leaders, Bishop/Branch Presidency, Family Home Evening, LDS Primary, LDS Seminary, LDS Singles, LDS Sunday School, LDS Young Men, LDS Young Women, Literacy Specialist, Melchizedek Priesthood Leaders, Priesthood, Primary Presidency, reading charts, Relief Society, Relief Society Presidency, scripture reading chart, Secretary - all, Special Needs, Teacher (adults), Teacher (youth/children), Young Men Presidency, Young Women Leaders

Jennifer Smith

November 19, 2013

Use these wordstrips to help students see the relationships between Lehi and other writers mentioned through the Book of Omni.

LDS Printables

Abinadom, Amaleki, Amaron, Chemish, Enos, Jacob, Jarom, LDS Seminary, lehi, Nephi, Omni, Teacher (adults), Teacher (youth/children)

Jennifer Smith

November 19, 2013

This file can be used to have students summarize For example: “Imagine you are Enos. What would you tweet about your experience with prayer.” or “Imagine you are one of the shepherds who saw angels at Christ’s birth. What would you tweet?” You can even ask students to draw a picture they may have snapped to go along with the tweet.

LDS Printables

Come Follow Me, Enos, Family Home Evening, LDS Primary, LDS Seminary, LDS Singles, LDS Sunday School, LDS Young Men, LDS Young Women, Priesthood, Relief Society, scripture tweet, social media, Special Needs, Sunday School Presidency, Teacher (adults), Teacher (youth/children), teaching techniques, teaching tips, Twitter, Young Men Presidency, Young Women Leaders

Jennifer Smith

September 30, 2013

This is a silhouett version of the Christus Statue with some alterations for ease of printing.

LDS Printables

Activities Directors, Activity Day Leaders, Bishop/Branch Presidency, Camp/Youth Conference Director, Christus, Clerk, Emergency Preparedness Specialist, Employment Specialists, Family History Specialists, Family Home Evening, Jesus Christ, LDS Primary, LDS Seminary, LDS Singles, LDS Sunday School, LDS Young Men, LDS Young Women, Literacy Specialist, Melchizedek Priesthood Leaders, Missionaries (ward/stake), Music Director/Leader/Chairperson, Priesthood, Primary Presidency, Relief Society, Relief Society Presidency, Secretary - all, silhouette, Special Needs, Sunday School Presidency, Teacher (adults), Teacher (youth/children), Visiting Teaching Leader, Young Men Presidency, Young Women Leaders

Jennifer Smith

August 9, 2013

I am subbing in Sunday School this week, and I think I am going to use the 1845 proclamation referenced in the text to teach a little gospel doctrine. I may not. Still deciding :) At any rate, here are a couple of handout versions you could use in your classroom. I’ve broken the document out into sections to make it easier to locate certain passages during teaching. For example,…

Read more

Jennifer Smith

May 6, 2013

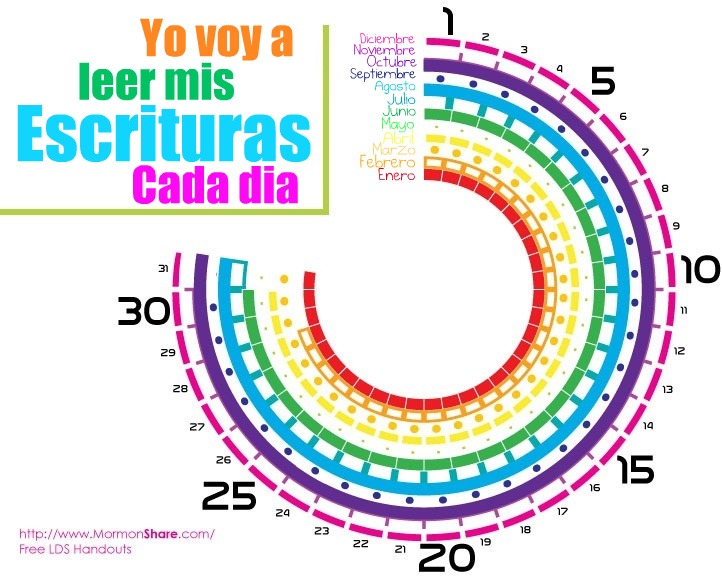

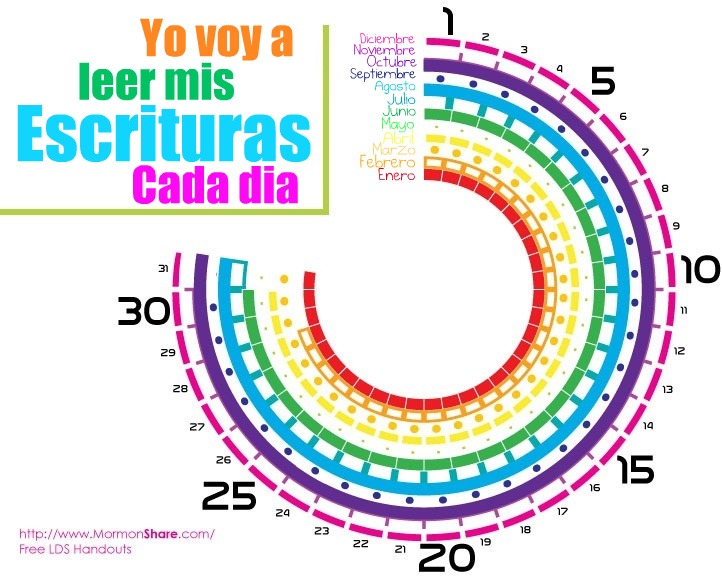

I found the original image in English but I needed it in spanish, so I edited and thought it may be helpful for other people too!

LDS Printables

Español, LDS Seminary, Missionaries (ward/stake), Primary Presidency, reading charts, Relief Society Presidency, scripture reading chart, Secretary - all, Spanish, Sunday School Presidency, Teacher (adults), Teacher (youth/children)